Understanding the Process of Oil-to-Gas Conversion

Outline and Why Oil-to-Gas Conversion Matters

If you are considering shifting from oil heat to natural gas, you are likely weighing cost, comfort, and environmental impact all at once. This article begins with a clear outline and then dives into practical detail, so you can understand the mechanics, compare energy and efficiency, evaluate costs and emissions, and plan a smooth, code-compliant project. Before the nuts and bolts, here is the map you will follow:

– How the conversion unfolds: assessments, permits, equipment, venting, and safety.

– The energy story: fuel characteristics, AFUE, condensing versus non-condensing systems, and distribution losses.

– Cost and emissions comparisons: up-front budgets, operating math, carbon factors, and risks.

– Implementation and maintenance: timelines, quality checks, and future-proofing strategies.

Why it matters now is straightforward. Many oil-fired furnaces and boilers installed decades ago are reaching the end of their useful lives, and they often operate at seasonal efficiencies between roughly 70% and the low 80s, depending on age, maintenance, and system design. Modern gas systems, especially condensing models matched to low-temperature distribution, can achieve AFUE ratings in the 90s under the right conditions. That efficiency gap, combined with differences in fuel pricing per unit of heat, can translate into meaningful savings over time. Beyond bills, there is the emissions angle: per unit of useful heat, natural gas typically emits less carbon dioxide than heating oil, although upstream methane leakage must be part of an honest assessment. For many households, the appeal is a mix of cleaner combustion at the appliance, steadier supply, and integration with modern controls.

Still, conversion is not a flip of a switch. You will need a utility line or an alternative gas source, proper sizing, venting updates, combustion air provisions, and electrical and control integration. Local codes and inspections ensure safety, and a careful commissioning ensures the system lives up to its ratings in real conditions. In short, think of oil-to-gas conversion as an energy upgrade project rather than a simple swap: planning is your lever for dependable comfort and long-term value.

The Process: From Site Assessment to Commissioning

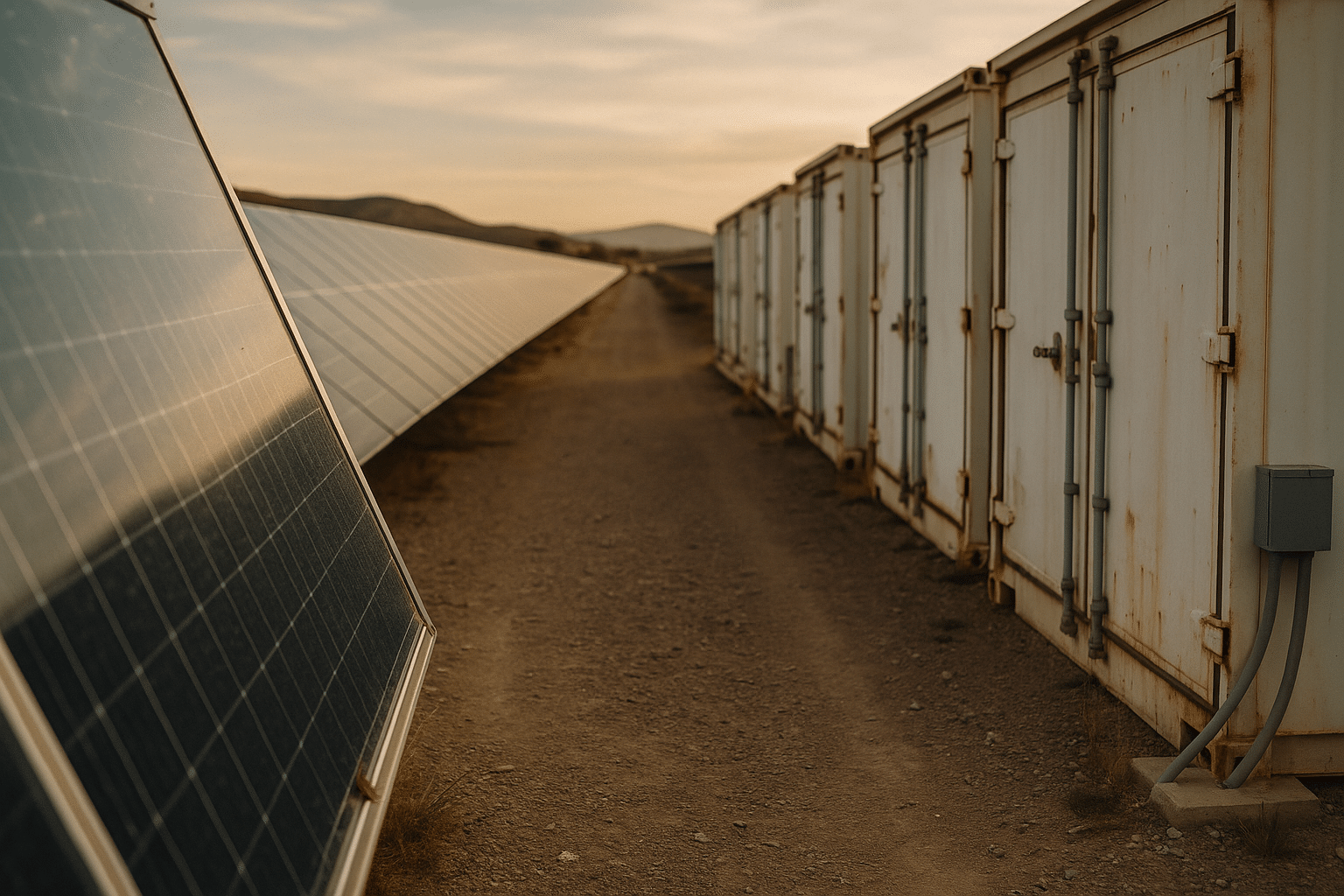

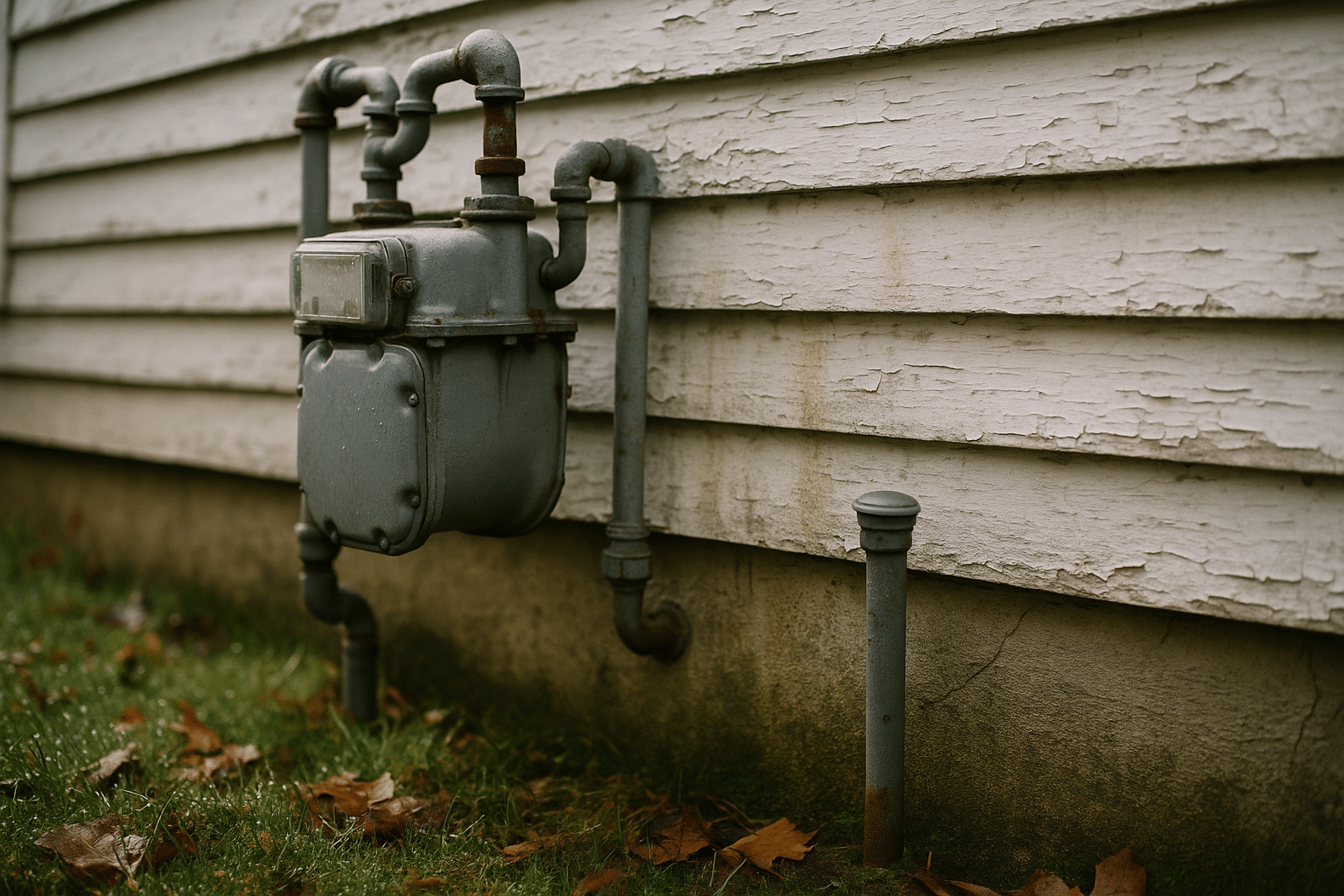

Successful conversion starts with a thorough assessment of your building and the existing system. A professional will evaluate the heat load (based on climate, envelope, and square footage), the condition and type of distribution (ducted air or hydronic radiators/baseboards), and the suitability of the mechanical space for new venting and combustion air. Just as important, they will verify whether a gas service is available to your property and what it takes to bring it from the street to the meter location. If no utility line exists, the discussion shifts to alternatives, timelines, or other efficiency pathways.

– Site assessment: heat-loss calculation, duct or hydronic review, and space for equipment/venting.

– Gas service: utility coordination, meter placement, trenching or routing, and any easements.

– Permits and code: mechanical, gas, electrical, chimney/vent approvals, and inspections.

Equipment selection follows sizing: furnaces and boilers should be matched to the calculated load, not just the nameplate of the old oil unit. Right-sizing avoids short cycling, improves comfort, and supports higher efficiency, especially with condensing units that thrive on longer, lower-temperature operation. Venting is a pivotal choice. Some systems require a lined masonry chimney; many modern high-efficiency models vent with sealed plastic or stainless piping through a sidewall or roof, drawing combustion air directly from outdoors to keep the mechanical room at neutral pressure.

Piping and controls integration come next. For a hydronic system, installers may reuse existing distribution while adding pumps, mixing valves, or outdoor reset controls to modulate water temperature. In ducted systems, attention shifts to supply and return duct integrity, filtration, and airflow, ensuring the new furnace meets its rated performance. Electrical work supports ignition, fans, pumps, and smart thermostats. After leak checks and pressure tests, commissioning begins: technicians verify gas pressure, adjust combustion with an analyzer, confirm vent draft (or sealed vent integrity), measure temperature rise or delta-T, and calibrate controls for typical winter conditions.

– Safety checklist: gas leak test, CO monitoring plan, combustion tuning, and verification of clearances.

– Documentation: equipment manuals, warranty registration, permit sign-offs, and commissioning reports.

– Owner orientation: filter changes, purge procedures (for hydronic), thermostat scheduling, and service intervals.

Treat commissioning as the last 5% that delivers the first 50% of your satisfaction. A well-commissioned system runs quieter, cycles less, and achieves closer-to-rated efficiency—benefits you will notice in comfort and consistency the first cold snap after the upgrade.

Energy Fundamentals and Efficiency Metrics That Matter

Oil-to-gas conversion is, at its core, an energy problem framed by physics and climate. Heating oil contains roughly 138,000 BTU per gallon (higher heating value). Natural gas is commonly billed per therm, where 1 therm equals 100,000 BTU; by volume, about 1,037 BTU per cubic foot is a typical reference. The raw energy content, however, tells only part of the story. What you feel in the living room is delivered heat, which depends on appliance efficiency, distribution losses, and your home’s envelope performance.

– AFUE (Annual Fuel Utilization Efficiency): seasonal measure that accounts for on/off cycling and standby losses.

– Condensing vs. non-condensing: condensing models capture latent heat in flue gases by running at lower return temperatures, which can push AFUE into the 90s under favorable conditions.

– System vs. steady-state: a lab number may not match field results if ducts leak, radiators are imbalanced, or control settings are off.

Consider an example. Suppose your oil boiler at 82% AFUE consumes 800 gallons per year. The input energy is about 800 × 138,000 = 110.4 million BTU. Useful output is 110.4 × 0.82 ≈ 90.5 million BTU. To provide the same useful heat with a 95% AFUE gas boiler, the input required is 90.5 ÷ 0.95 ≈ 95.3 million BTU, or roughly 953 therms in a typical winter. This back-of-the-envelope exercise helps you convert fuel bills into comparable units and estimate future consumption with a new system.

Distribution can tilt the math. Leaky ducts in unconditioned spaces may lose 10% or more of the heat before it reaches occupied rooms; hydronic systems may waste energy via constant high water temperatures and uninsulated piping. Upgrades such as duct sealing, insulation, outdoor reset controls, and proper radiator balancing can yield tangible gains without changing the fuel. Envelope measures—air sealing, attic insulation, and window improvements—reduce the load itself, allowing smaller equipment and longer, steadier runtimes that boost efficiency and comfort.

Finally, controls define how the system behaves day to day. Programmable or smart thermostats can trim runtime, but thoughtful scheduling and reasonable setpoints matter more than flashy features. Outdoor reset on boilers, two-stage or modulating gas valves on furnaces, and verified airflow/water flow all help align the system with real-weather conditions. When equipment, distribution, and controls work together, efficiency stops being a number on a brochure and becomes a lived experience of even heat and lower bills.

Costs, Emissions, and Risk: A Balanced Comparison

Upfront costs for oil-to-gas conversion vary widely with site conditions and scope. Budget lines can include utility service extension and meter installation, trenching or piping on the property, new appliance and venting, chimney lining if needed, control wiring, removal or decommissioning of the oil tank, and permit and inspection fees. In many markets, a whole-home conversion with standard equipment commonly falls within a mid-four-figure to low-five-figure range, but unique constraints—long service runs, structural modifications, or extensive duct/hydronic work—can push totals higher.

– Operating math: compare $/MMBtu, not just $/gallon or $/therm. Divide price by energy content and adjust for AFUE to estimate delivered-heat cost.

– Example approach: Delivered cost = (Fuel Price per Unit ÷ BTU per Unit) ÷ AFUE × 1,000,000 for $/MMBtu of useful heat.

– Payback thinking: savings from lower fuel and maintenance costs offset the project cost over time; results depend on your climate, building, and local pricing.

Emissions are a critical part of the decision. Typical carbon dioxide factors are around 161 pounds CO2 per million BTU for heating oil and about 117 pounds CO2 per million BTU for natural gas. Using the earlier example, the oil system consuming 800 gallons emits roughly 800 × 22.4 ≈ 17,900 pounds of CO2 per year. The gas system supplying about 95 million BTU would emit about 95 × 117 ≈ 11,100 pounds. That simple comparison suggests a notable reduction, but there is an important caveat: methane, the primary component of natural gas, is a potent greenhouse gas if leaked before combustion. Minimizing upstream and local leakage—through robust utility practices and tight on-site connections—helps preserve the emissions advantage.

Other risks and benefits round out the picture. Gas appliances generally offer cleaner combustion at the point of use and may require less frequent nozzle or filter maintenance compared with some oil setups. On the flip side, dependence on a utility adds a new stakeholder to your comfort; rare supply interruptions, meter work, or planned maintenance are handled on a shared schedule. Safety is non-negotiable either way: install carbon monoxide alarms, keep clearances to combustibles, and schedule annual service to verify combustion quality and vent integrity. Insurance and local rules may also influence decisions about removing or abandoning existing oil tanks, especially if they are underground, so factor that into your plan early.

In short, the financial and environmental calculus can be favorable, but it is not one-size-fits-all. Use your own load, current bills, and realistic equipment options to model outcomes, and treat incentives as helpful sweeteners rather than the basis of the decision. A measured, transparent analysis tends to lead to durable satisfaction long after the installers drive away.

Planning, Maintenance, and Future-Proofing: A Practical Conclusion

Think of your conversion as a project with a beginning, a middle, and a long tail of ownership. Start by collecting good information: past fuel use, square footage, insulation levels, and any comfort complaints like cold rooms or noisy ducts. With that in hand, secure multiple written proposals that include load calculations, equipment model classes (efficiency tier, capacity, venting type), scope of work, permits, and a commissioning plan. Ask each contractor to explain how the system will operate at part load on a typical winter day, and how controls (thermostat type, outdoor reset, staging or modulation) are configured to support steady, efficient performance.

– Before work: confirm permits, schedule utility visits, plan for oil tank removal or safe abandonment, and clear work areas.

– During work: insist on pressure tests, combustion analysis, and documented airflow or hydronic balancing.

– After work: obtain commissioning reports, warranty registrations, and a maintenance schedule, and test carbon monoxide alarms.

Maintenance sets the arc for long-term efficiency. For furnaces, change or clean filters regularly and verify proper static pressure and airflow. For boilers, have a technician check combustion, clean heat exchangers as needed, and verify that supply and return temperatures allow condensing operation when applicable. Hydronic systems benefit from periodic air purges and inspection of pumps and expansion tanks; ducted systems gain from sealing and insulating any runs that cross unconditioned spaces. A brief annual visit catches small issues before they grow into efficiency losses or comfort problems.

Future-proofing is about leaving doors open. If you plan to add a heat pump later for shoulder seasons or full electrification, consider a hybrid-ready design today. That might mean keeping supply temperatures modest, sizing ductwork for lower airflow noise at higher efficiency, or adding hydronic mixing controls. Smart thermostats can coordinate multiple stages or sources without drama, but simplicity wins over complexity—choose features you will actually use. Envelope upgrades amplify any mechanical investment: air sealing and insulation reduce load, stretching every therm further and calming the runtime profile that drives comfort.

For homeowners and small property managers, the takeaway is straightforward. A careful oil-to-gas conversion can be one of the top options for improving heating efficiency, stabilizing operating costs, and lowering on-site emissions, provided it is planned and commissioned with rigor. Use the methods here to compare fuels on equal footing, ask pointed questions about venting and controls, and schedule maintenance that protects your investment. With a realistic plan and clear expectations, your next heating season can be quieter, cleaner, and easier to live with—comfort built on sound engineering rather than guesswork.